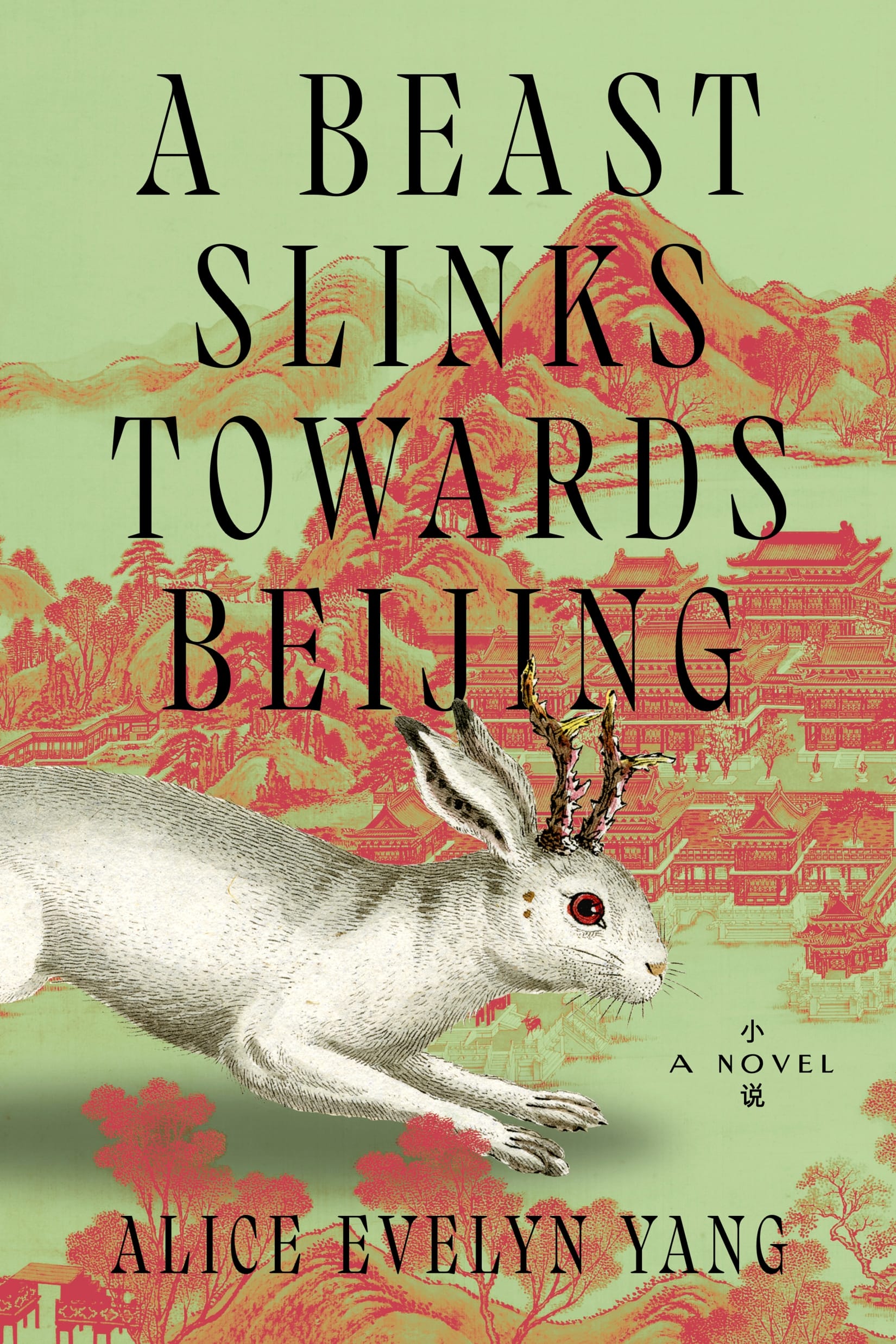

'A Beast Slinks Towards Beijing' confronts family, trauma and history

Alice Evelyn Yang’s debut explores a fractured father-daughter relationship shaped by the lasting pull of inherited memories.

Qianze is just living her life in New York when a phone call about a weird Chinese man standing on the porch of her childhood home in Virginia summons her home. It’s her father (who she calls Ba). She hasn’t seen him in 11 years after he walked out on her 14th birthday, and he’s different now.

In “A Beast Slinks Towards Beijing,” a moving debut by Alice Evelyn Yang, Qianze and her father go from not speaking at all to being stuck temporarily living together in her one-bedroom apartment. Ba is frail and often confused. All he has with him is a duffel bag which contains two handles of liquor, three packs of cigarettes, some clothes and a couple personal belongings. His new chain-smoking habit in her AC-unitless apartment creates a toxic fog that seeps into her room. Despite this, Qianze is hopeful at first; maybe he’s here to apologize? But between cigarettes and drinking himself into a stupor, he says he has a prophecy for her, and he won’t leave until he delivers it. He just can’t remember what it is.

The novel continues in rotating points of view between Qianze, Ba, Ba’s adolescent self (Weihong), and Ba’s mother, Ming. Over the course of the book, their family history unfolds through the Chinese Cultural Revolution, Weihong’s eventual abandonment of his family, and Qianze’s life without him.

“Long ago there’d been a collection of birthday candles and coins in fountains and stray eyelashes and dandelion seeds all spent on Ba’s return. That he might come back to the Myrtle House and tell them that it was all a mistake, that he’d gotten lost, that he’d been kidnapped,” Yang writes in Qianze’s point of view. “Instead, Ba had barreled back into her life — a bull in a Chinatown apartment — with his blathering and his baijiu truths …”

There’s a version of this novel that could have been all about their strained relationship and learning to navigate it. There’s another version of this book that could have been strictly about the Cultural Revolution with touches of fortune-telling and fantasy. Typically, it’s either/or, and it’s rare to see them together. But “A Beast Slinks Towards Beijing” contains multitudes, and Yang bridges the genres well.

What do parents owe to their kids and vice versa? How does one learn to carry on after trauma? The novel asks these questions and more, but there are no clear and easy answers. Even after the final reveals, there’s some ambiguity that keeps this reviewer up at night.

Qianze, in the tradition of 2nd generation Asian Americans, longs for roots and something to look back to before her and her nuclear family, but her parents both refuse to talk about it.

“That was another life. We are American now. We don’t need to hold on to old things,” her mother tells her.

But looking back is important to her. She yearns for it in a way her mother doesn’t understand, but any second-generation immigrant would.

It’s easy to think of events like the Cultural Revolution as history that happened a long time ago, but Yang brings both the events and their echoes into sharp clarity. The actions Weihong’s mother took to survive have consequences for him, and the same is true for his own daughter. It’s all tied together, and the past isn’t really passed.

“A Beast Slinks Toward Beijing” is a beautiful and heartbreaking reminder that our parents have histories and complex lives of their own, and therefore we do have roots, even if we don’t know about them yet, and it joins a growing collection of novels like “River East, River West,” and “Homeseeking” which explore those roots and stories unflinchingly. Alice Evelyn Yang is a gifted storyteller and one to watch.