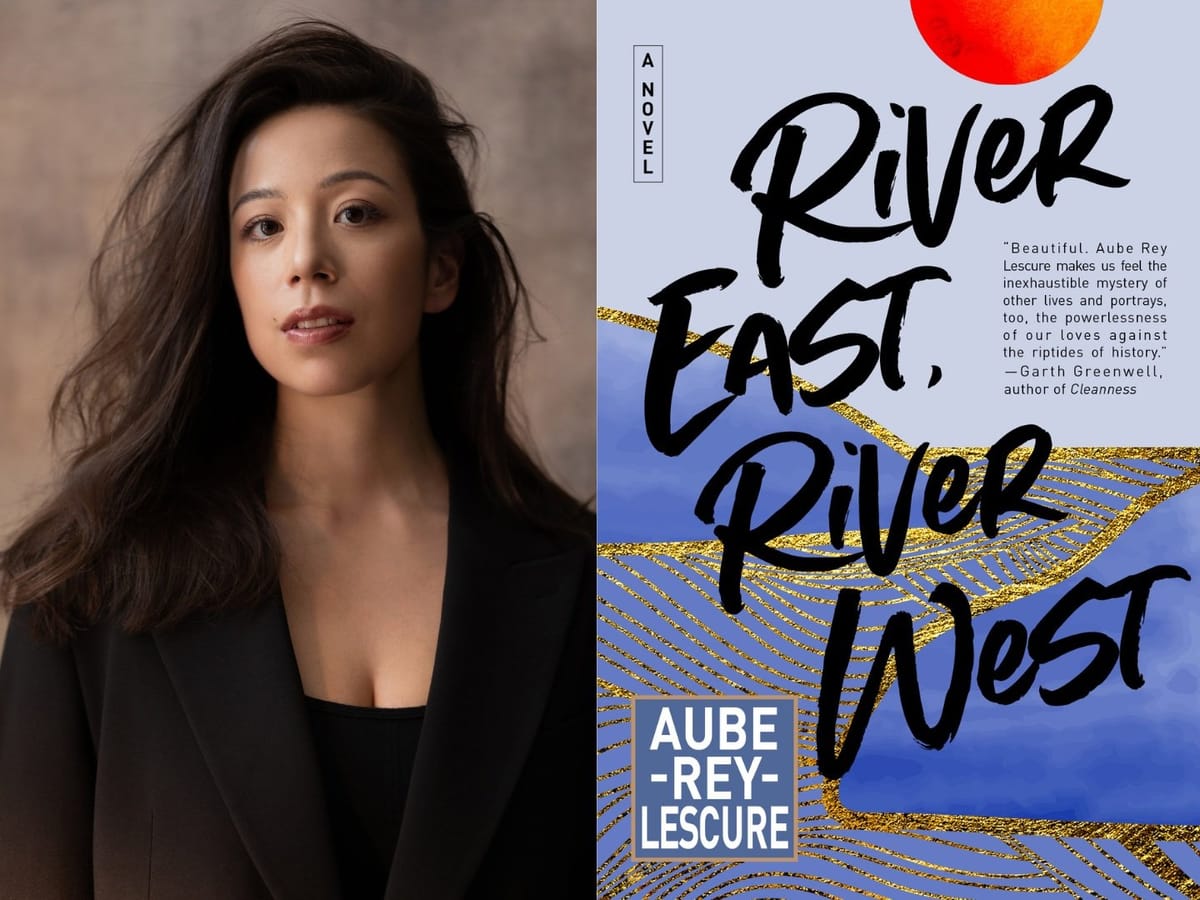

Inside the parallel worlds of Aube Rey Lescure’s ‘River East, River West’

Set in 2007 Shanghai and 1985 Qingdao, “River East, River West” alternates between a mother’s and daughter’s perspectives, highlighting the massive cultural shifts in China both after the cultural revolution and the late aughts.

In Aube Rey Lescure’s debut, “River East, River West,” Alva is a biracial 14-year-old with a Gilmore Girls-esc relationship with her white mother, Sloan. They’re partners in their somewhat unconventional life in China — that is until Sloan announces that she’s marrying their most recent landlord, Lu Fang.

Set in 2007 Shanghai and 1985 Qingdao, the novel alternates between Alva and Lu Fang’s perspectives, highlighting the massive cultural shifts in China both after the cultural revolution and the late aughts.

“River East, River West,” is out Jan. 9. SPRHDRS caught up with Rey Lescure to chat about the book.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

What inspired you to write “River East, River West?”

Definitely my own experience growing up between Dalian and Shanghai until age 16. It's no secret that the book is highly autobiographical. I grew up with a French expat mom and a Chinese father, but it was mostly my mother who raised me as a single mom. We would rent apartments and move from city to city.

I went to Chinese public school until I was 14, and then I went to two years of international school in Shanghai. That transition to the international school was a huge culture shock. Even though I am biracial and had an expat mother, I identified as Chinese and went to school with other Chinese children. When I had an immersion into expat culture, I was horrified by the condescension and indifference that expats were showing towards Chinese people and their host country.

That shock of seeing those two parallel worlds — the highly regimented Chinese school system I was coming out of and expat teenagers who were kind of living their best lives in the worst ways stayed with me.

I feel like there's an intoxication that Westerners often experience coming into modern Asian metropolises, and that can take on a very icky manifestation –– I'm definitely not immune to it myself. I was missing an expat novel that focused on critiquing this ick factor more than it was just being like This is so glamorous! Expats in Asia!” without being critical of it. So I set out to write it.

I know some authors prefer to keep a separation between themselves and their fiction. How do you feel about people potentially reading your experiences into the novel?

The biggest, most dramatic plot points and events actually really didn't happen to me — like I never had a Chinese stepfather who was our landlord who we moved in with.

But authenticity matters a lot to me, and part of me does care that readers know that, even though the plot points might be fictional, what I'm trying to say in terms of social commentary is coming from a place of observations and experiences that I've lived or seen. I care about this book as a coming of age story and family drama, but first and foremost, it’s a social book.

How did you make translation decisions for Mandarin phrases in your book?

It was very much instinct. One of the biggest challenges in this book is the whole artifice that most of it takes place in China between Chinese characters who are supposedly speaking Chinese, but obviously the book is written in English.

Some of them [Chinese characters] are easter eggs I buried intentionally for Chinese speakers. One example is when Alva gets on the school bus for Shanghai American school and talks to the Chinese woman who’s checking off names. There’s a line of Chinese characters that literally says, “Uhh … my name is Alva,” including the Chinese “uh.” Then the lady calls out after her and says, “Oh, your Chinese is so good!” Which is what you usually would say to a foreigner who just attempted speaking Chinese.

This line isn't particularly important for a reader to know exactly what was said, but maybe contextually it can be kind of a wink that something troll-y just happened in this linguistic exchange.

In the middle of the book, we hear two versions of the myth behind the Mid-Autumn Festival about Chang’e and Houyi: one where Chang’e’s assent to the moon is heroic because there’s a bad guy trying to steal it and another where Chang’e is selfish and ascends because she can’t resist the temptation. In childhood, I’d only heard the selfish version, so it was really surprising to revisit the story and rethink how I’d been led to maybe misjudge this character. Since “River East, River West” is set in the China of your childhood, I’m wondering if there’s anything you revisited for the book that feels similar?

What comes to mind is 1989 and how that was totally not a part of my childhood growing up. There’s this moment when I was a teenager in a car with my mom and two other foreigners talking about 1989 and Tiananmen.

They were clearly referring to something enormous, and I was overhearing that conversation for like 30-40 minutes, and I was like what on earth are they talking about?

Then I asked my mom, and she was so shocked like “What? Obviously! The Tiananmen Square Massacre!” But I was like mom, you raised me in China, and you put me in the Chinese school system. How can you be surprised that I know absolutely nothing about this?

There was this deep sense of betrayal that my mom could be shocked that I didn't know — all the blind spots people can have. Even as partners who are mutually dependent on each other, there's this big disconnect between even a biracial child and fully caucasian mother and how they're treated in China and experiencing the country.