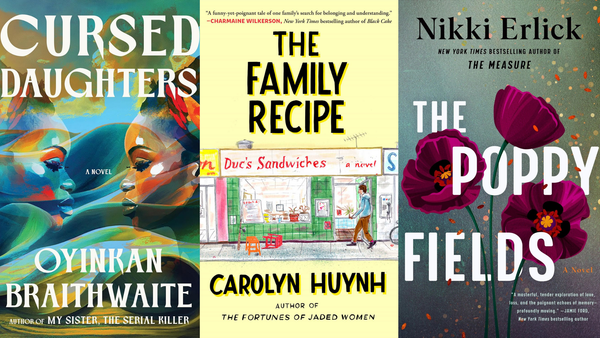

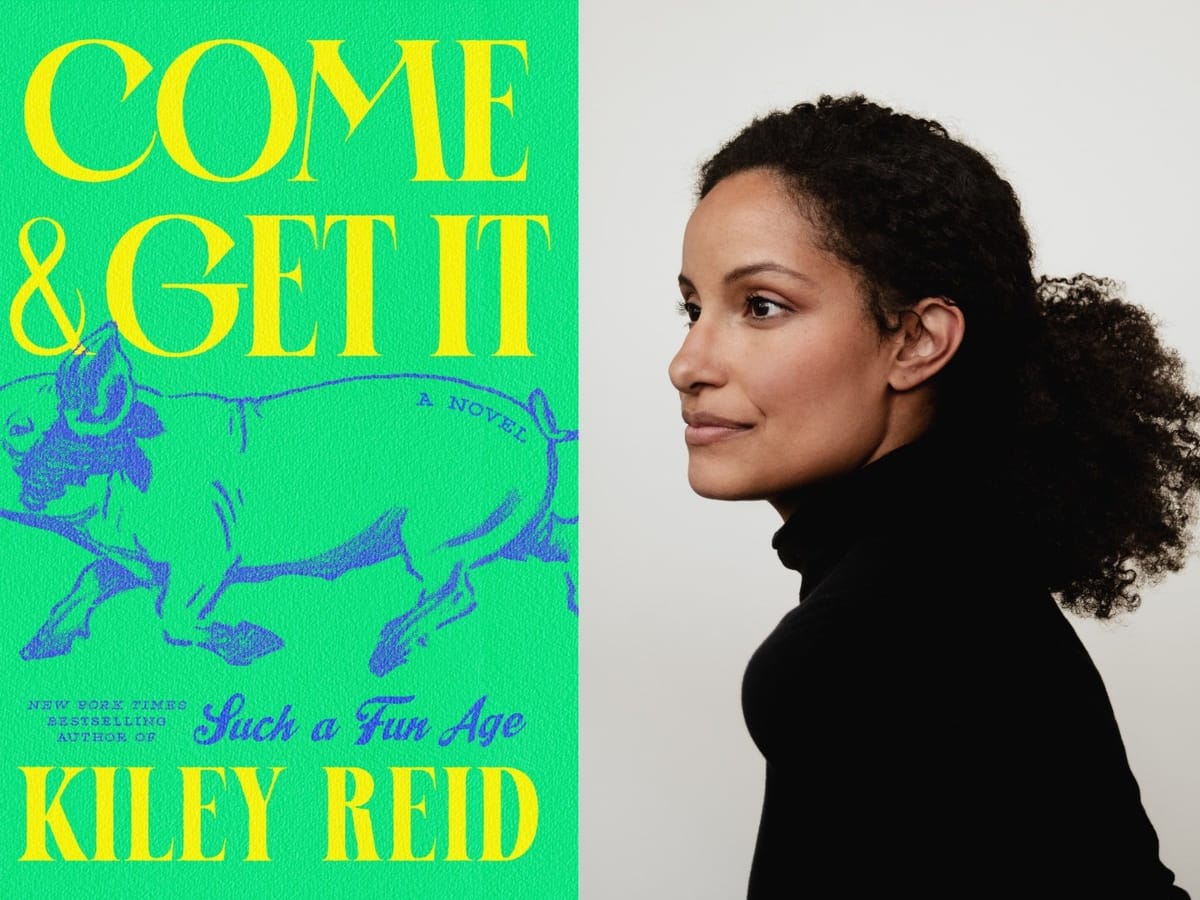

College, class and money moves in Kiley Reid’s ‘Come and Get It’

Kiley Reid’s sophomore novel “Come and Get It” brings readers to contemplate money, early adulthood and relationships.

In Kiley Reid's sophomore novel, “Come and Get It,” Millie Cousins is a super-senior at the University of Arkansas who is trying to save for a house; she's working as an RA to save the money. And when she gets an unusual opportunity from a visiting professor and journalist Agatha Paul to make some money on the side to help her with research for her book, it's a no brainer — of course she can help set up some interviews about weddings with the residents in her dorm.

Agatha sits in Millie’s dorm room on Thursday nights and eavesdrops on her residents as a “follow up” to the interviews they agreed to do with her. Agatha’s research topic has changed from weddings to money. Sure, it blurs the lines of research ethics, but it's not like she's actually doing anything wrong, Millie reasons. It's just a formality –– plus, Millie offered. She’s allowed to have guests. The situation escalates as Agatha writes articles for Teen Vogue based on these “interviews,” revealing and sometimes embellishing personal details about the girls and their lifestyles.

It’s hard to sum up the rest of the novel. It’s set during the 2017-2018 school year, and there’s a group of three suitemates who don’t get along. One of whom, Kennedy, is having a particularly difficult time adjusting as a transfer student. She moved to Arkansas to get away from her past, but it’s not going as planned. Similarly, Agatha left her long term partner, a dancer named Robin, in Illinois, and has some baggage of her own.

But none of this is really the point. Contrary to Reid’s award-winning debut novel, this book isn’t as plot driven. With “Come and Get It,” Reid captures the feeling of being a messy, new adult and the uneven starting places we all come to that milestone with. Some people have generational wealth, others rely on their partners, still others have to make their own way, and regardless of what support you do have, being an adult is hard and full of things you can’t control.

The book shines through its characters, even when they are a little ridiculous. Jenna, one of the girls who is interviewed and then eavesdropped upon, nonchalantly talks about the “practice paycheck'' (read: allowance) she gets from her father’s orthodontics business. If you think that sounds like fraud, so does Agatha.

As the story progresses, Reid’s otherwise reasonably realistic set-up takes a turn for the absurd. It can feel a little abrupt, but it’s not unpleasant. For lovers of campus novels with a sardonic tone like “Disorientation,” “Come and Get It” is a propulsive novel where the author reveals backstory at just the right time, giving readers the opportunity to change their first impressions of the characters.

At first, Kennedy seems like a spoiled girl whose mom pampers her with so many things, they can’t be stuffed into her assigned dorm room. But after seeing her struggle with her past and have a hard time making friends, readers will feel for this character who is “never sure about what she should be doing, how she should do it, or exactly when.”

The college roommate drama plays out in a way that is so petty that it feels realistic — until it goes off the rails. Dishes left in the sink and differences in lifestyle leading to aggressively passive stand downs and pranks are the exact kind of thing that feels so ‘high school’ (or whatever period of life feels so young to you these days that you should be above it), but you also just can’t let go.

“Come and Get It” also represents a burgeoning trend of writing about people of color in Arkansas. In recent years, we’ve had “Minari,” (part of) “The Bestiary,” and last year, the New York Theatre scene saw not one but two plays about people of color in the state.

Arkansas is often shorthand for talking about a place where there isn't anything, especially for people of color. “Come and Get It” complicates that in an interesting way. Reid has clearly done her research and incorporated names and details based on actual businesses in the area, and the novel captures a tension about the place that was true in 2017 and is even more salient now. Northwest Arkansas is changing, and the place it’s becoming might not be what outsiders expect. It’s picturesque –– think expensive bike trails and hipster cafes –– but it’s also complicated.

With rent increases in Northwest Arkansas tripling the national average last year and home prices jumping by 26%, it feels nostalgic to think of a time that one could buy a house by the university with only 10% down on $102,000 –– even if someone had died in it –– as Millie attempts to. It would have been a stretch in 2017, but it’d be completely impossible now given the housing crisis in the region. Setting the book pre-pandemic might be practical for a lot of reasons, but for a novel so focused on exploring the way wealth impacts people in their early 20s, it feels like a missed opportunity not to talk about the pandemic and how different people weathered the economic downturn associated with it.

Still “Come and Get It,” brings readers to contemplate money, early adulthood and relationships in an interesting way. Behind it all, Reid reminds us about the complex lives people are living, often without us noticing.