Isa Garcia's journey of home, grief and renewal

Isa Garcia finds resilience through loss, showing us that through pain, there is room for joy, connection, and growth.

Welcome back to "Unmasking," a column dedicated to exploring the lives of artists through a different lens — one that focuses more on their being than their doing: when they are simply listening, studying, rehearsing, encouraging, and living.

"Who are you without your masks?" This was the first note I wrote, which became this column a few years ago. After a year-long hiatus, I want to emphasize how much I needed this column as a prompt for my journey. I offer it back now because our truths can be valuable despite the often harrowing and cathartic process of unmasking them. If not for ourselves, then perhaps for others. These conversations have helped me cope during a time that challenged my relationships with home, grief, and renewal. Continuing this dialogue feels imperative.

So, I begin again with one of the most beloved and respected authors in the Filipino writing community: Isa Garcia.

Isa Garcia is a writer, teacher, and creative from the Philippines. She has been dedicated to storytelling for over a decade, creating a body of work that spans books, zines and essays. Her collections — like “The Light Years,” “Like Lines on a Map,” “Notes from the Border” and “Sad Girl City” — capture the rawness of human connection, loss, and healing. Alongside her work as an author, Isa has also spent years shaping the next generation of writers, teaching and nurturing new voices. These days, her focus has expanded into building equitable spaces for creativity and growth, such as “Line Breaks”— a writing space for writers and non-writers—and “Play/Ground”, a creative arts space for adults to reconnect with their inner child.

Ride Home

I met Garcia for the first time in her home, tucked away in the quieter townhouses of Metro Manila. Despite the early hours, she greeted me warmly and invited me to settle in. There’s something deeply intimate about stepping into someone’s home — each corner tells a story, and each object holds a memory. Garcia’s space, a blend of soft sunlight filtering through the windows and the cool contrast of air conditioning, offered a sense of peace that immediately put me at ease. I was happy to speak to her again recently.

“I’m in a busy season right now,” she said as we exchanged pleasantries. “I’ve been thinking a lot about aging — how it shows up in my body, in the photos I look at, and yet, I still feel so young at heart. My future still excites me.”

Her words were measured and tender, showing the generosity and kindness I’ve known her for.

“Hope feels like a youthful thing, and I’m grateful I still carry it inside me,” she said.

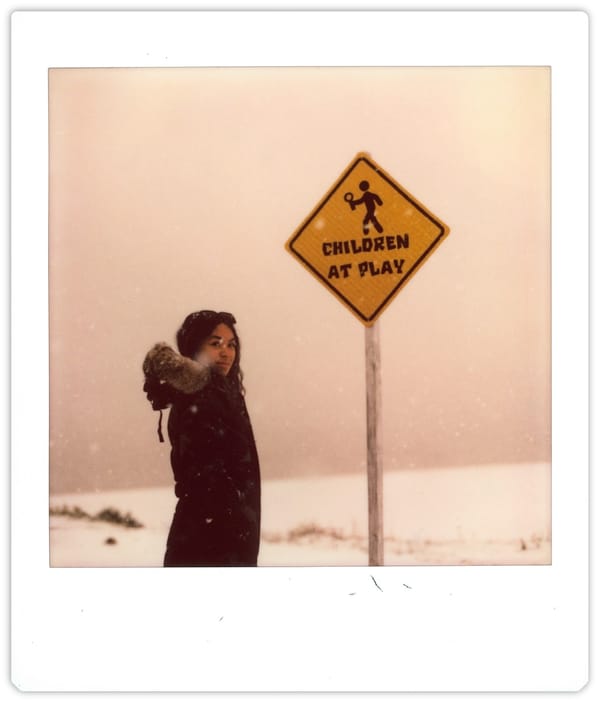

At 36, the writer shares a home with a friend and fellow artist. Born in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, she spent much of her life moving from place to place, and it’s easy to see how her transient lifestyle has shaped her work.

"If I had never moved back to the Philippines, who knows if I would’ve even pursued writing?” she mused.

Her journey started with a moment of encouragement in 7th grade.

“My English teacher told me I could be a writer, and I believed her. If that marked the chain of events that brought me to this interview, then I am suspect to believe that,” she paused and sat with nostalgia between us.

“I could only have become a writer here, in the Philippines. This soil, these roots, home, itong wika na hindi ko pa talaga naiintindihan ng husto (this language that I don't fully understand yet) – my relationship with words just wouldn’t be the same if it did not start here,” she said.

These sentiments are woven through her books: “The Light Years,” a collection of vignettes that are honest, tender glimpses into her life, especially the enduring power of friendships. And “Like Lines on a Map,” a collection of essays reflecting on the relationships that have shaped her, both fleeting and permanent.

Garcia added, “There are parallel lives — Isa in Malaysia, Isa in America, Isa in other cities. I wonder about them, but I don’t mourn them. The life I have now is enough.”

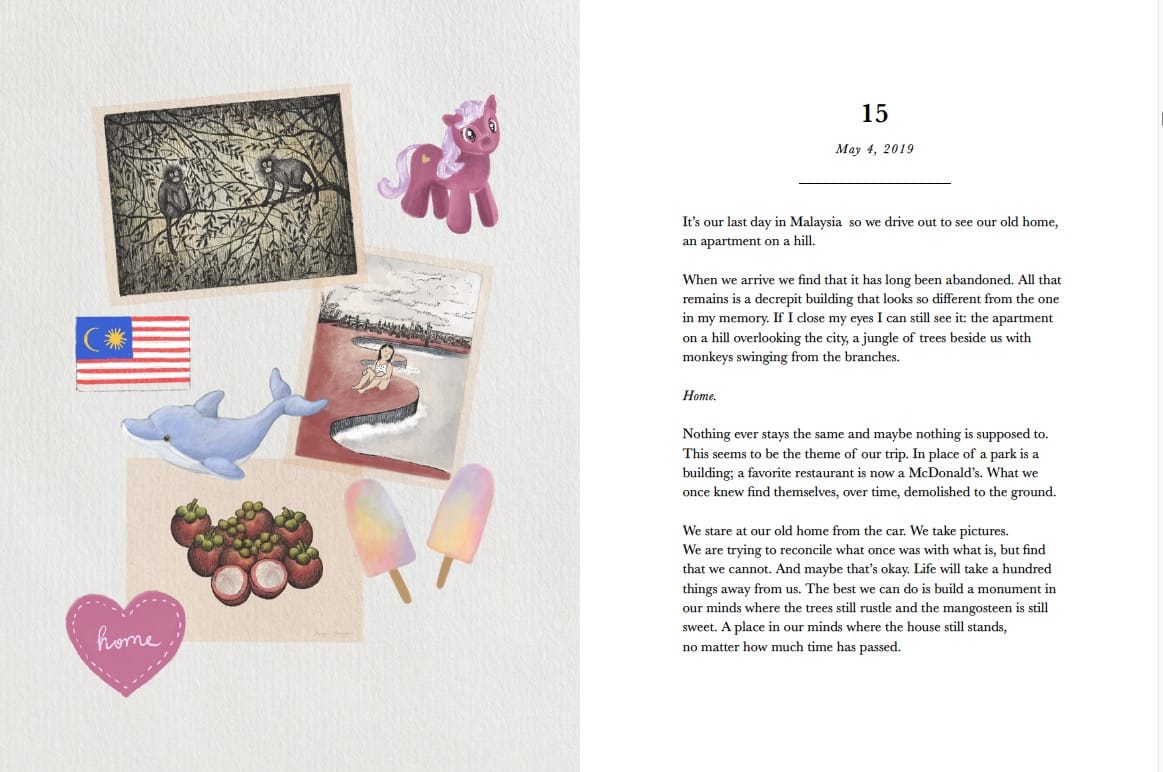

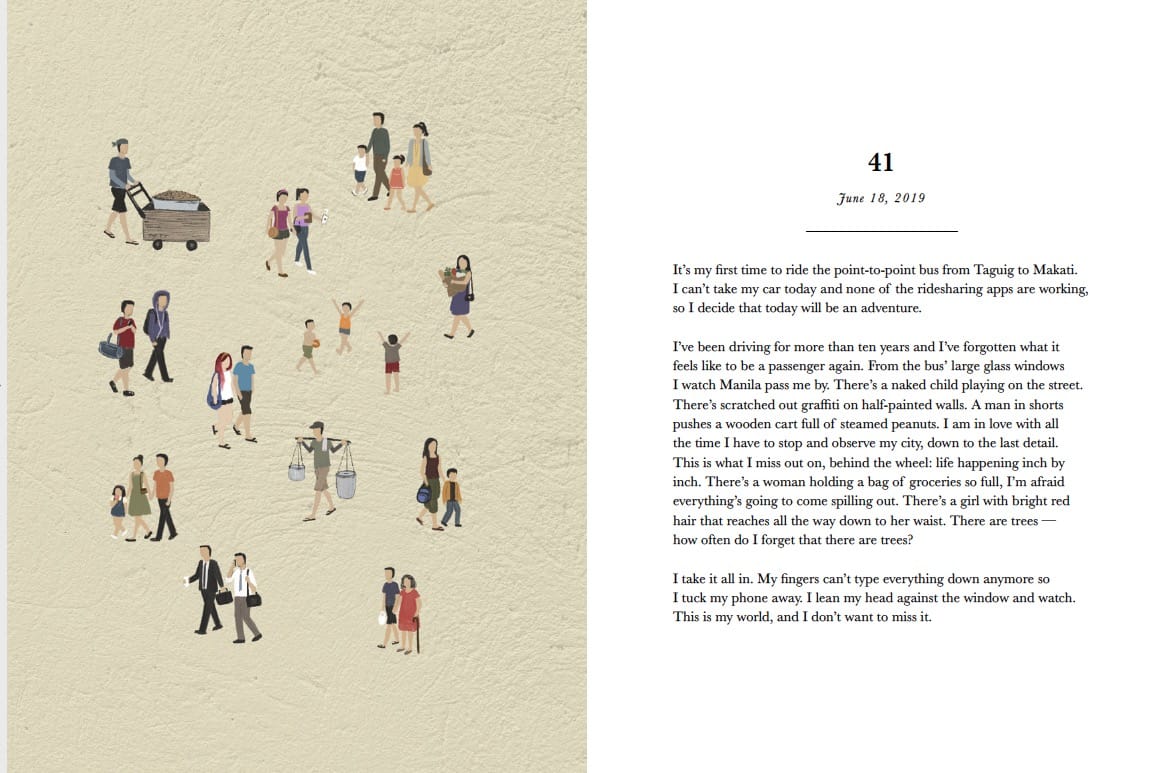

Excerpts from Isa Garcia's "The Light Years." Images courtesy of Isa Garcia.

Grief At The Door

As I sat in Garcia’s living room that day, I was struck by how she moved at a good pace. A few writers and friends joined us, turning our meeting into a hangout-slash-writing workshop. We gathered around her table, sharing food, drinks, and our stories. In Garcia’s space, sharing stories, reading poems, and making art are as important as the air you breathe. And while we threw punchlines in passing to maintain a sense of balance, Garcia’s presence is deliberate. She listens, laughs, reflects, and when it’s her turn to share, her words are always considered.

That night, she reflected on grief and loss — a theme she had been exploring since the death of her father, Dennis Garcia, a member of the legendary Filipino band, Hotdog, and who wrote “Manila”.

“Grief doesn’t feel familiar to me at all,” she said to me. “Even five years after my father’s passing, it’s something I’m still learning to understand. Nothing prepares you for the permanence of death.”

I agreed, she’s right. I also once thought I was securely bound for life until my grandparents passing. I wasn’t so alert to grief and my capacity for it until then.

She went on, “Grief is the great equalizer. It comes for all of us, and it ruins us. But finding the language for that pain, for that loss — that’s why I write. I want others to have words to hold onto when they experience their unspeakable loss.”

In her work, she refuses to offer easy answers or silver linings. She doesn’t sugarcoat grief or pretend it will “get better.” Instead, her writing holds a mirror to its rawness.

“The work we’re called to do as humans is to accept that suffering is part of life,” Garcia said. “But it has the potential to transform into something beautiful if we let it. The defiance comes later after we’ve let ourselves feel.”

This vulnerability is woven into “Sad Girl City,” a collection of journal entries that captures her first year of mourning. Despite being one of her lesser-known works, I was surprised that it was her current pick as a favorite. Garcia holds it dear.

“It’s a sadder, angrier, more human book,” she admitted. “I read it again this year and felt so much love for the girl who wrote it.” It’s clear that Isa has accepted grief — its inevitability, its weight — and allowed it to transform her, to transcend her.

Play/Ground

And in transcendence, there is renewal. As she roots herself in publishing and academia, Garcia’s creative journey has evolved.

“I loved teaching long before I became a published writer,” she said. “Teaching is the art of communicating ideas clearly, and writing is the same. It’s about breaking the heart open. It’s a masterclass in compassion, boundaries, empathy, and communication.”

Recently, she launched Play/Ground, a space blending writing, teaching, and creative arts. The focus here is rest, joy, and discovery.

Garcia now views creativity through a different lens.

“I want Play/Ground to be a space where we can look at big emotions, at grief, from the perspective of joy. Not to diminish pain but to recognize that pain is not our only story. Pain is not our final story,” she said.

There’s wisdom that comes with age, and Garcia embraces it fully.

“The great thing about getting older is that you care less about being profound. You make more room for absurdity, for silliness. Play, fun, and spontaneity are pathways to well-being — a revolutionary realization for me as an adult,” she said.

I saw what she meant as I reeled in the few years left of my 20s.

When asked where her playground was growing up, she cites camping in her mom’s bathroom alongside their sampayan, an outdoor space to hang their laundry.

“I used to sit there at times and watch the clouds. I think I ultimately found my deepest safety in reading, in stories, in books,” she said.

In her 30s now, she’s roughly the same.

I stayed back at her place afterward, and we shared dinner before my ride back to the city's central business district. When I ask her about what she’s learned to appreciate in her hometown, Isa reflects on the contradictions of Manila.

She reflected on her father’s iconic song, “But his Manila is different from mine,” she said. “My Manila is chaotic, corrupt, and crowded. It’s dirty and unsafe. But still, my Manila is filled with people planting beautiful things — artists, teachers, poets, caregivers, environmentalists, visionaries.”

Garcia’s father’s iconic song, beloved by so many Filipinos, is a testament to his legacy. And she’s right — there’s a love-hate relationship with this city, one that’s impossible to deny.

"Manila has a fierce, beating heart," she added. "At its core are its people, filling it with culture, art, and hope. She’s an underdog — but don’t count her out. She can still surprise you."

I laughed as she shares this anecdote because it rings true — the transit life, the language gap, and the intersections and contradictions she spoke of all reflect parts of me. Garcia’s perspective on home, art, grief, and storytelling reminds me that amidst pain, there’s always room for joy, possibility, and growth. In the tension between sorrow and hope, she’s found her voice and a creative and personal renewal that continues to unfold — an unyielding, great reveal.