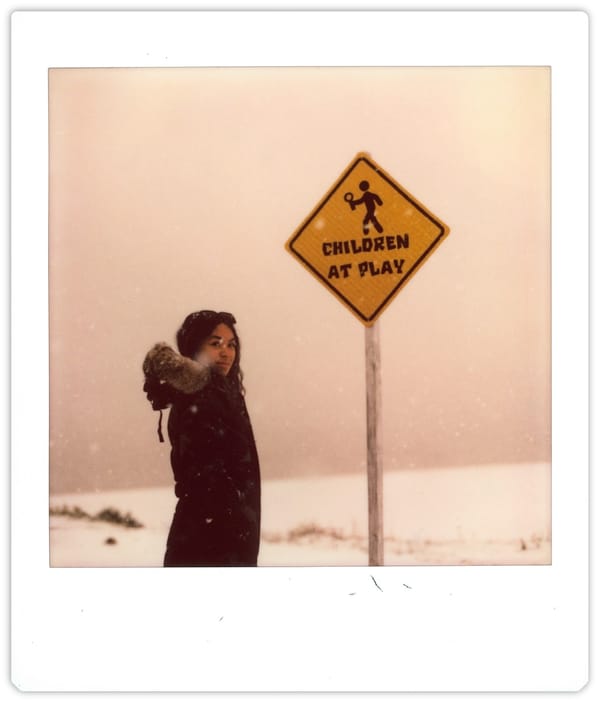

Reclaiming Lineage: The sacred dance of SAMMAY Peñaflor Dizon

SAMMAY Peñaflor Dizon channels ancestral memory, ritual and community to forge a path for healing.

SAMMAY Peñaflor Dizon channels the power of lineage, land and identity, weaving a path that is deeply personal, political and profoundly embodied. Dizon is a Filipinx American choreographer and interdisciplinary artist whose work bridges ancestral remembrance, ritual and community.

Grounded beginnings

Raised in the crosscurrents of culture and community in Carson, California, Dizon was never far from rhythm. The daughter of Philippine immigrants and the product of a working-class Los Angeles neighborhood, Dizon’s earliest memories are steeped in sound: church choir harmonies, Tagalog films on VHS and the laughter of multigenerational, multicultural gatherings.

“My parents have been singing in the choir since I was 6 years old,” they say. “I was a soloist in their choir and eventually joined the youth choir on my own accord. Singing was my first love — it still is, secretly.”

But it was through dance that Dizon found an embodied language for something larger. By age 7, Dizon choreographed routines for their community’s Filipino fiestas. By 10, they trained in a hālau. What began as performance evolved, over the years, into sacred practice, one where choreography served as a conduit and movement as memory.

That shift began in earnest during their senior year at the University of California Berkeley, through a performance residency led by Māori contemporary artist Tiaki Kerei. Their collaborative work, “Turangawaewae,” which means “standing place,” invited dancers to explore ancestral land and identity while occupying the unceded territory of the Ohlone people.

“It was world-shattering for me, in the best way,” Dizon recalls. “I was at a crossroads: would I continue the life I was living now that I knew what I’ve actually always known?”

Their time at Berkeley introduced them to mentors and kinfolk in the world of diasporic performance, including Afro-futurist conjure artist amara tabor-smith, Brazilian master teacher Rosangela Silvestre and hip-hop pioneer Rennie Harris. These experiences rooted them further in what they call “re-membering” through dance: the process of retrieving lost or suppressed lineage by way of the body.

Healing through movement

Dizon describes their body as a vessel of ancestral dialogue, a site of inherited wisdom that defies the limitations of language.

“My body remembers a life before capitalism, before colonization, before the binary,” they say. “It remembers the ecstasy of living in reciprocity with land. It knows it was once seen as sacred.”

Their performances are acts of both resistance and remembrance. Choreographic offerings that seek to reunite the fragmented parts of their cultural and spiritual being.

“The more I dance to re-member, the more possibility I find to live freely in this body, even on this strange stretch of the Earth’s timeline,” they say.

Dizon often names their mother and grandmothers in their bio. A deliberate act of honoring the matrilineal line that made them. Their mother, born in Albay, Bicol — home of the majestic and volatile Mayon Volcano — is the eldest of eight and the only one who immigrated to the U.S.

“My mom is the griot of the family, the keeper of stories and memory,” they say. “The essence of my matrilineal line is everything you think of when you see Mount Mayon: everlasting beauty, reverence for what you cannot control and what will certainly outlast you.”

Their roots trace through Bikol, Kapampangan and Ilokano lineages. Though their relationships with each lineage vary in proximity, they are no less vital.

“There was certainly a time when all of this felt severed,” they say as they reflect on their grandmothers, who are now in the spirit realm. Dizon says their grandmothers are "wildly different and both generous."

"They’ve helped me deepen my relationship to our ancestors and the feminine divinity that guides me,” they say.

Behind the performances lies a process steeped in preparation — spiritual, emotional and communal.

“I clear space inside of me to receive the messages,” they say. “I call in my ancestors. I write. I set intentions. I prepare myself and those walking with me to truly hold what the work demands. That’s what it means to be a doula for art.”

Transmuting generational trauma is central to their practice, but they emphasize that healing is lifelong, nonlinear and deeply personal.

“I’m not a psychologist, but I’ve spent more than a decade peeling back layers,” they say. “And that’s still just scratching the surface. I come from generations of resilience, and I know that my role is part of that ongoing, intergenerational mission.”

Embodying the future

As they approach their 33rd birthday, Dizon moves forward with a clarity that is both grounded and expansive. As a choreographer of new futures shaped by ancestral knowing, artistic rigor and an unwavering devotion to collective liberation, these days, rest is non-negotiable.

“You can’t f— with my rest,” they laugh. “This past year has been transformational. I’ve finally embraced solitude and sacred rest as a source of clarity and power. Rest informs every decision I make.”

“I am from volcano people,” they remind us. “That fire will always find a way.”

Looking to the future, Dizon dreams of abundance and care.

“I want my family to inherit a world that’s more livable, equitable and free,” they say.

Dizon acknowledges their evolving relationship with identity, particularly the layered tension of being Filipinx American.

“I used to leave off the ‘American’ part,” they admit. “But the more I took ownership of the privilege of being born and raised in the U.S. — instead of resenting it — the more I realized the importance of naming that complexity.”

Often the only Filipinx person in creative spaces, they learned to navigate with humility and accountability.

“There is medicine at the crossroads,” they say. “The intersections of our experiences are where new futures are seeded. I try to honor similarities inside of differences. This, to me, is the core of pagkikipagkapwa: to extend our relationship to self beyond our ancestry alone.”

Editor's note: This story has been updated to clarify that SAMMAY Peñaflor Dizon's grandmothers have both passed away.