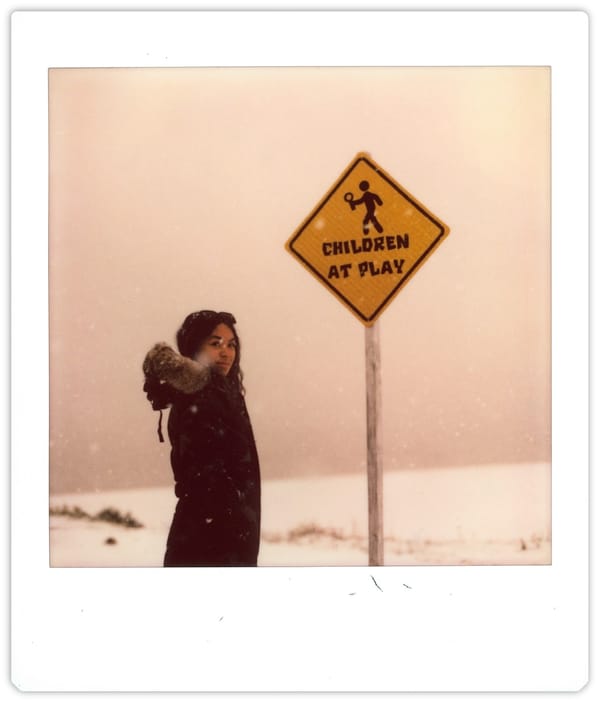

Kristin Villanueva at the heart of ‘The Pitt’

Kristin Villanueva shines in "The Pitt," revealing the soul of care work and bringing representation with depth and humanity.

The joke I tell lately — half in jest, half in resignation — is that after the year I’ve had, I could probably pass as an intern on “The Pitt.” Between my father’s hospital stays and my ongoing shift as his caregiver, I’ve learned enough medical jargon to survive rounds and earn the hours of a resident minus the paycheck. If the show ever needs another Filipina on staff, my patient-care credits should count for something.

In truth, this year has taught me how hospitals hold both grief and grace in the same breath.

So when “The Pitt” arrived, a medical drama that felt less like fiction and more like reflection, I found myself watching with a strange sense of recognition, which is both its own comfort and heartbreak. There, in the chaos of the ER, was something achingly familiar. And at the heart of it all is a character named Princess, played by Kristin Villanueva, one of the show’s most grounded and magnetic presences.

Now Emmy-decorated and globally acclaimed, “The Pitt” has become the series that treats care work with the dignity and complexity it deserves. But speaking with Villanueva wasn’t just about the show’s success or its awards-season glow. It was, for me, a full-circle moment to talk with someone who portrays the world I’ve been living in, and to hear her reflect on care both as performance and as practice feels imperative.

The choreography of care

When I catch Kristin Villanueva, she’s in the thick of something new.

“I’m doing well. Currently occupied with the wins and woes of being pregnant,” she tells me.

There’s an ease that seems to mirror her life these days, poised between celebration and responsibility, public and personal. After all, we birth many things. Not just children, but callings, characters, and versions of ourselves we never expected. For Villanueva, one of those births came in the form of Princess, the quick-witted nurse she now brings to life in “The Pitt.”

Her path, like many artists’, wasn’t linear.

“Before ‘The Pitt,’ I was lucky enough to have my temp job turn full-time as a program manager at a tech company,” she recalls. “My husband and I were traveling a lot. We were actually in London when I got the audition.”

But when she read for the role of Princess, something in her shifted.

“I told my reps that I was going to be more selective of Filipino nurse auditions because I’d already played them as very minor parts,” she says. “I didn’t want to perpetuate that practice of only having them in the background. But when I got the invite to audition, the way the casting team described her was very interesting to me. A force not to be messed with, animated and spunky, whipsmart with a dose of sarcasm, speaks six languages. And with her name alone, I thought someone in the writing team did their research.”

There’s an understated pride when she says this, from being seen with nuance. On screen, Princess is not a caricature of care; she’s its articulation. Villanueva plays her with precision that only someone who’s lived between service and survival could understand.

“When I first stepped into that ER set,” she admits. “I didn’t think about the representations. What was immediate were my lines, learning the choreography, knowing where the cameras were. It’s not until I have the technical aspects down when the lived experiences come to life.”

She pauses and reflects, “I drew a lot from my eight years of waiting tables. The urgency, the way you move around a table with your servers and bussers, but this time around a patient, moving around doctors and nurses. The way you have to anticipate what they need, the way you don’t show emotion regardless of what you actually feel.”

In that translation from service to performance, Villanueva captures something profound: the choreography of care, the invisible labor of anticipation.

“In quieter scenes,” she adds, “I always think about Filipino immigrant nurses who left their families in the Philippines to seek a better life abroad. How painful it must be to take care of other people while not being able to physically take care of their loved ones back home.”

It’s that ache, complex and generational, that gives the show its heartbeat. And perhaps why, for those of us who’ve lived inside hospital corridors, Villanueva’s presence doesn’t just feel like representation but rather recognition.

Finding ourselves in ‘The Pitt’

When the show premiered, I remember being caught off guard three minutes into the first episode when two nurses, both Filipina, were speaking Tagalog in the middle of the ER. It was a small moment that carried the weight of generations. Spending the last years moving between the languages of illness and intimacy — Tagalog murmured in hallways, English spoken to doctors — hearing that felt like permission to exist fully, even in the most sterile environments.

Villanueva understood that resonance, too.

“That opening scene didn’t stir me at all until I saw the episode. My goodness, that was so impactful. Even to me, who actually read the scene and shot it. And I thought it was one of the signs saying that this is not going to be your typical medical show,” Villanueva says.

Her instinct proved right. The show has since been praised for its ensemble, a constellation of brilliant actors. Villanueva credits that atmosphere for shaping her craft in unexpected ways.

“My background is theatre,” she says. “So I had a lot to learn from our camera operators and thank God they were so patient with me and eager to teach.”

She laughs when she says this, but there’s real affection in how she speaks about the people she works with. Everyone is her teacher.

“I continue to learn a lot from the med techs, the props department, the assistant directors and background actors,” she adds. “It’s striking how she describes filmmaking as collective choreography.”

When I ask her what the show has left behind in her, she smiles. She takes a moment before continuing.

“Princess has been the closest to my personality compared to all the other roles I’ve played, but she has way more ownership of her confidence, skills, sexuality and fun-ness than I do with my own. So that’s something to strive for,” she responds.

She pauses again to translate something larger: “The show, in general, has reminded me that there is so much I don’t know about people and what’s going on in their lives. That perhaps an irrationally angry person can be dealing with grief, or a seemingly cold person can be dealing with their own cancer diagnosis, or someone who jokes a lot may actually have PTSD.”

Listening to her, I thought again of the hospital hallways I’ve walked, of the nurses who held me together through the longest nights. It’s easy to assume, to judge, to forget the storms people carry behind their uniforms or smiles. Come to think of it, I’ve met so many Princesses. Villanueva reminds me that care, in all its forms, is less about fixing and more about witnessing.

The person beyond Princess

Beyond the set, beyond the scrubs, who is Kristin Villanueva when the camera stops rolling? Who is she when she steps out of Princess’ world and into her own?

“I’m a very curious person,” she tells me. “A life-long learner.”

Then, as if tracing the little pockets of joy that fill her days, she starts to list her knowledge bank: learning to play poker, watching war documentaries, movies from the ’70s, snorkeling in the Caribbean, surfing baby waves.

Her words gather momentum the more she speaks: bar games, stationery stores, hole-in-the-wall restaurants. She tells me she’s become more private as she’s gotten older.

“I enjoy more one-on-one time than parties,” she adds. “But I’ll always dance on the dance floor.”

We talk then about the small things that bring uncomplicated joy. She lights up recalling how a friend remembered her favorite cheesecake, or how a production assistant always brings her apple juice when she’s “fading” on set. She tells me about a stage manager who became her pen pal and how receiving a handwritten letter in the mail makes her day.

Hearing these pockets of her life reminds me that unmasking isn’t only about revealing pain or peeling back vulnerability. It’s also about honoring delight, humor and the ordinary things that keep us alive. In Villanueva’s world, joy comes in apple juices, cheesecakes, letters and laughter.

The next season

As the series readies its second season, Villanueva describes returning to the set not with pressure but with presence.

“Princess is more vibrant this season, you see more of her personality. Part from the writing, part from my confidence,” she says, laughing. “Now that I know how to find the lens.”

What she loves most, though, is the reunion: the familiar choreography of movement, of breath, of people working in sync.

“It was just nice,” she says simply, “to be back with friends on set.”

Outside the hospital walls, her artistic hunger remains wide-ranging.

“I’ve always daydreamt of a Filipino season of Narcos,” she tells me — a story rooted in power, survival, and consequence.

She still misses the cadence of Shakespeare, the layered pauses of Chekhov, the intimacy of new plays by Annie Baker or Amy Herzog. There’s an actor’s restlessness in her voice. And when I ask what role she’s learning to live with, one that feels her most significant yet, she doesn’t hesitate: “Becoming a mother.”

From the fluorescent urgency of an ER to the dim quiet of a nursery, from tending to scripts to tending to a new life, the choreography remains; only the scene changes.

As our conversation closes, I’m reminded that “The Pitt” — for all its alarms and emergencies — has never just been a hospital. It’s a mirror. One that reflects the grace and mess of our attempts to care for others, for art, for ourselves.

In every ward, every set, every home, we’re rehearsing the same lesson: that care isn’t a single act, but a way of being with one another.