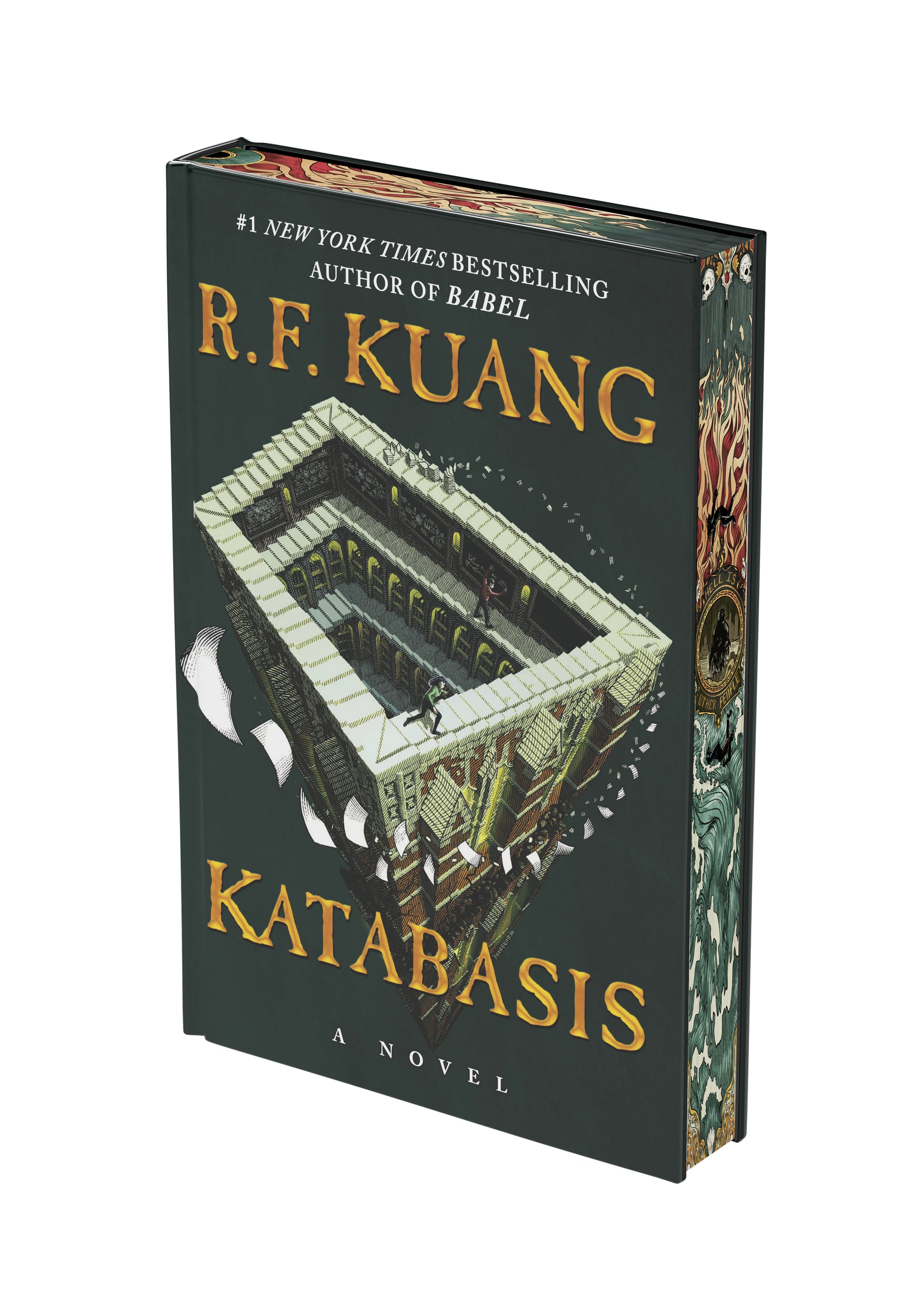

R.F. Kuang turns academia into a descent through hell in ‘Katabasis’

Kuang’s newest release is a departure from the gossip-filled thriller that was "Yellowface" toward a hellscape, exposing the cost of academic ambition.

What would you do to live your dream?

In “Katabasis,” the newest novel by R.F. Kuang, Cambridge Ph.D. student Alice Law sacrifices half her remaining lifespan to go to hell to rescue her advisor who has died in a magical accident. He’s no angel, and she has no delusions about that, but without him, she has no committee chair, which means she won’t be able to defend her dissertation, which means that she won’t be able to graduate, which means that she can’t get a job in the field that she had sacrificed everything for.

Unfortunately, her academic rival, Peter Murdoch, has decided to do the same. Begrudgingly, they partner up and journey down to hell together (the ancient Greeks would call this a "katabasis,” hence the name of the book). The place they find themselves in is a mix of Buddhist hell, the underworld described in Greek mythology, Dante’s hell and a university campus.

Many early readers and reviewers have noted the deeply researched and academic nature of the book. To really get it, one would have to be conversant with multiple intellectual traditions, systems of faith, philosophy and mathematics. Kuang switches between quoting scholars, the Bible, and theoretical principals with ease like only a true academic could.

But whether you get the references in part or in whole, it's not hard to draw parallels between the world of the story and our own world. Alice has sacrificed everything to achieve her dreams of working in the field of Magick. She’s paid her dues, worked long hours, dealt with a terrible boss and played department politics, yet her place in the field is still not guaranteed for reasons outside her control. It’s a career not unlike writing, art or even academia in our own world.

“Everyone told magicians in training to at least consider careers in other fields before they went on the job market,” Kuang writes in the book. “‘Alt academia,’ they called it, like it was some punk and rebellious lifestyle, like failing at the single thing you’d been trained to do made you cool.”

It makes sense that Kuang, who has studied at Oxford, Cambridge and Yale, would invent hell modeled after a university campus. Like many of the underworlds of her references, there are different courts to move through, and each one (at least in the beginning) is a distinct place on campus. The court of pride is a library. Desire is a student center. While the journey to find their advisor is enough to keep readers moving through the book, Kuang shines in her grappling with more existential questions: What constitutes punishment? What is the purpose of a place like hell in the first place? How do we as people make up for the terrible things we do to each other? Is that even possible?

It should be noted that Kuang isn’t the only contemporary writer playing with the idea of hell. There’s that one really popular TV show with lots of philosophy mixed in (no spoilers, but if you know, you know), Lore Olympus, Leigh Bardugo’s “Hell Bent,” and many more. Maybe hell as a premise helps us make sense of the world as a cruel and unfair place. Maybe it’s a reaction to political instability and the unprecedented times we find ourselves in. Regardless, the problems Alice and Peter face in hell sometimes are more revealing about the lives they left behind.

Hell, as the popular adage and the sprayed edge of the book itself suggest, might be other people, but “Katabasis” reveals to us that the loneliness of living through hard things seemingly alone is a hell of its own. Alice and Peter are advised by the same bad person, playing the same rigged game of academia, and they’re both miserable.

But perhaps the real tragedy of the situation is that they think that the other person is the enemy, or at the very least their competition in a zero-sum game, when really, they’re the only people who can truly understand each other. This is largely due to the advisor who pits them against each other, but it can also be read as a metaphor for life in general right now. Things are bad, and they are not helped when different people, victimized in different ways, turn against each other.

As usual, Kuang shines in her world-building and character development, and though it’s a huge departure from the gossip-filled thriller/critique of publishing that was “Yellowface,” it also feels a lot more intimate than “Babel” or “The Poppy War.” The magic of this world isn’t just the pentagrams and logical proofs that Alice and Peter have to improvise to get out of traps and situations. The deeper into hell’s courts they go, the more the reader finds out about them, and this information changes the way we see their dynamic, motivations and even the earlier parts of the book.

At 560 pages, this book is a commitment, but it’s more like getting to know someone in all their flaws intimately. It goes, perhaps slowly at first, but it’s worth the journey.